Editor's note: This is a chapter excerpt from "CCDE Study Guide" by Marwan Al-shawi and published by Cisco Press.

A campus network is generally the portion of the enterprise network infrastructure that provides access to network communication services and resources to end users and devices that are spread over a single geographic location. It may be a single building or a group of buildings spread over an extended geographic area. Normally, the enterprise that owns the campus network usually owns the physical wires deployed in the campus.

Therefore, network designers typically tend to design the campus portion of the enterprise network to be optimized for the fastest functional architecture that runs on high speed physical infrastructure (1/10/40/100 Gbps). Moreover, enterprises can also have more than one campus block within the same geographic location, depending on the number of users within the location, business goals, and business nature. When possible, the design of modern converged enterprise campus networks should leverage the following common set of engineering and architectural principles:

■ Hierarchy

■ Modularity

■ Resiliency

Enterprise campus: Hierarchical design models

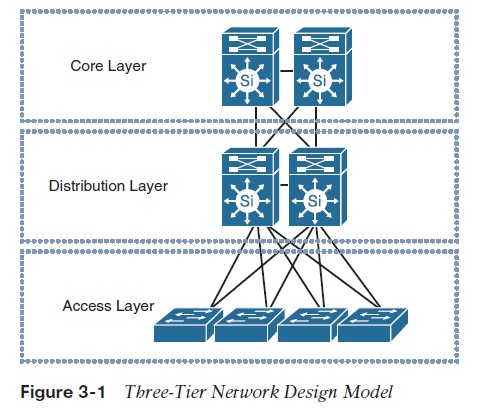

The hierarchical network design model breaks the complex flat network into multiple smaller and more manageable networks. Each level or tier in the hierarchy is focused on a specific set of roles. This design approach offers network designers a high degree of flexibility to optimize and select the right network hardware, software, and features to perform specific roles for the different network layers.

A typical hierarchical enterprise campus network design includes the following three layers:

■ Core layer: Provides optimal transport between sites and high-performance routing. Due the criticality of the core layer, the design principles of the core should provide an appropriate level of resilience that offers the ability to recover quickly and smoothly after any network failure event with the core block.

■ Distribution layer: Provides policy-based connectivity and boundary control between the access and core layers.

■ Access layer: Provides workgroup/user access to the network. The two primary and common hierarchical design architectures of enterprise campus networks are the three-tier and two-tier layers models.

Three-tier model

This design model, illustrated in Figure 3-1 , is typically used in large enterprise campus networks, which are constructed of multiple functional distribution layer blocks.

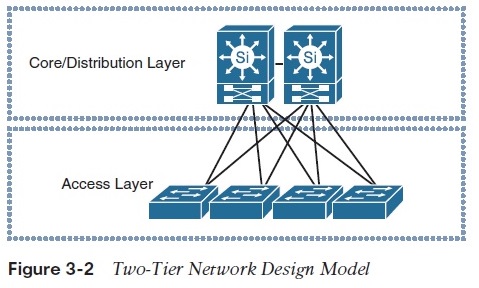

Two-tier model

This design model, illustrated in Figure 3-2 , is more suitable for small to medium-size campus networks (ideally not more than three functional disruption blocks to be interconnected), where the core and distribution functions can be combined into one layer, also known as collapsed core-distribution architecture .

Note: The term functional distribution block refers to any block in the campus network that has its own distribution layer such as user access block, WAN block, or data center block.

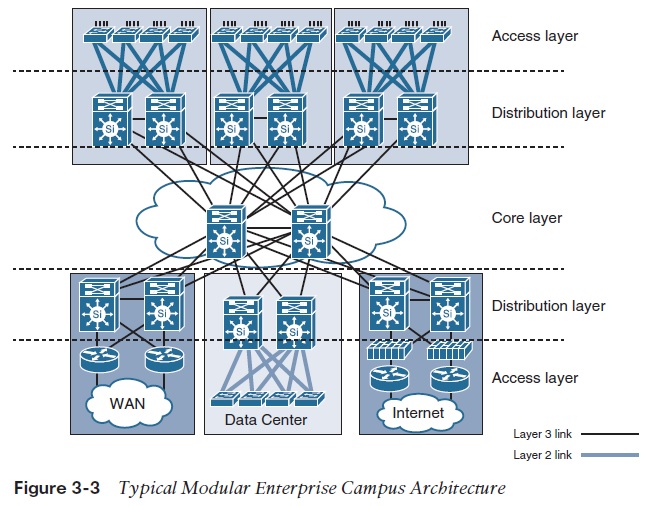

Enterprise campus: modularity

By applying the hierarchical design model across the multiple functional blocks of the enterprise campus network, a more scalable and modular campus architecture (commonly referred to as building blocks ) can be achieved. This modular enterprise campus architecture offers a high level of design flexibility that makes it more responsive to evolving business needs. As highlighted earlier in this book, modular design makes the network more scalable and manageable by promoting fault domain isolation and more deterministic traffic patterns. As a result, network changes and upgrades can be performed in a controlled and staged manner, allowing greater stability and flexibility in the maintenance and operation of the campus network. Figure 3-3 depicts a typical campus network along with the different functional modules as part of the modular enterprise architecture design.

Note: Within each functional block of the modular enterprise architecture, to achieve the optimal structured design, you should apply the same hierarchal network design principle.

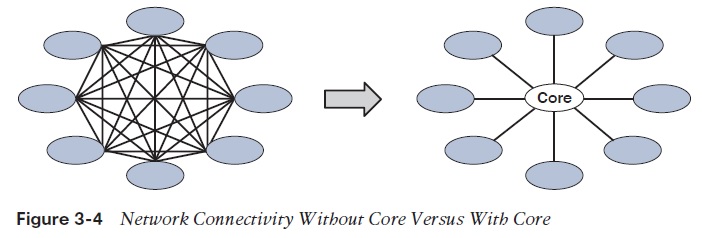

When is the core block required?

A separate core provides the capability to scale the size of the enterprise campus network in a structured fashion that minimizes overall complexity when the size of the network grows (multiple campus distribution blocks) and the number of interconnections tying the multiple enterprise campus functional blocks increases significantly (typically leads to physical and control plane complexities), as exemplified in Figure 3-4 . In other words, not every design requires a separate core.

Besides the previously mentioned technical considerations, as a network designer you should always aim to provide a business-driven network design with a future vision based on the principle “build today with tomorrow in mind.” Taking this principle into account, one of the primary influencing factors with regard to selecting two-tier versus three-tier network architecture is the type of site or network (remote branch, regional HQ, secondary or main campus), which will help you, to a certain extent, identify the nature of the site and its potential future scale (from a network design point of view).

For instance, it is rare that a typical (small to medium-size) remote site requires a three-tier architecture even when future growth is considered. In contrast, a regional HQ site or a secondary campus network of an enterprise can have a high potential to grow significantly in size (number of users and number of distribution blocks). Therefore, a core layer or three-tier architecture can be a feasible option here. This is from a hypothetical design point of view; the actual answer must always align with the business goals and plans (for example if the enterprise is planning to merge or acquire any new business); it can also derive from the projected percentage of the yearly organic business growth.

Again, as a network designer, you can decide based on the current size and the projected growth, taking into account the type of the targeted site, business nature, priorities, and design constraints such as cost. For example, if the business priority is to expand without spending extra on buying additional network hardware platforms (reduce capital expenditure [capex]), in this case the cost savings is going to be a design constraint and a business priority, and the network designer in this type of scenario must find an alternative design solution such as the collapsed architecture (two-tier model) even though technically it might not be the optimal solution.

That being said, sometimes (when possible) you need to gain the support from the business first, to drive the design in the right direction. By highlighting and explaining to the IT leaders of the organization the extra cost and challenges of operating a network that was either not designed optimally with regard to their projected business expansion plans, or the network was designed for yesterday’s requirements and it will not be capable enough to handle today’s requirements.

Consequently, this may help to influence the business decision as the additional cost needed to consider three-tier architecture will be justified to the business in this case (long-term operating expenditure [opex] versus short-term capex). In other words, sometimes businesses focus only on the solution capex without considering that opex can probably cost them more on the long run if the solution was not architected and designed properly to meet their current and future requirements.

For more on campus network design, download the full chapter and book index.