Open Source Vs. Proprietary: Time For A New Manifesto

Philosophical debates over OpenStack vs. vCloud or OpenDaylight vs. Cisco ACI miss the point. For IT, ideological purity is neither possible nor desirable

November 20, 2014

Get the new issue of Network Computing, distributed in an all-digital format.

Get the new issue of Network Computing, distributed in an all-digital format.

Contention between open source groups freely releasing code and commercial vendors capitalizing on proprietary products started the minute software became a profit-generating industry. The latest battleground? Enterprise data centers, with fights focused on cloud stacks, software-controlled networks, and big data systems. The lines are far from clear-cut. Established IT vendors incorporate open source code, APIs, and standards in their products. Startup companies are happy to commercialize public open source projects if they see demand. IT must take a pragmatic approach to software and vendor selection.

It's business, not dogma.

Unfortunately, human (and especially, engineer) nature being what it is, debates tend to take on a moralistic -- and occasionally anti-capitalist -- tenor, conflating open source software with idealized notions of liberty, community, and creative license. The tone was set early on by open source evangelist Richard Stallman, father of the Emacs editor and many other OS subsystems that were eventually subsumed by Linux. From Stallman's Gnu Manifesto:

"I consider that the Golden Rule requires that if I like a program I must share it with other people who like it. Software sellers want to divide the users and conquer them, making each user agree not to share with others. I refuse to break solidarity with other users in this way. I cannot in good conscience sign a nondisclosure agreement or a software license agreement."

Figure 1:

There are also cold, hard business and technical reasons why an open source development model makes sense, articulated by that other famous philosopher of the movement, Eric Raymond. Chief among them: software quality, security, reliability, and speed of development. In Raymond's view, open source replaces Brook's Law, which holds that adding manpower to a late software project makes it later, with Linus's Law: "Given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow."

Software vendors counter that without proprietary software and intellectual property protections, there's little incentive to invest and innovate. Both sides make valid points, and the fact is, open source projects like OpenStack, Open Daylight, Hadoop, and even core operating systems such as Linux and Android have been adopted and are funded by large IT vendors.

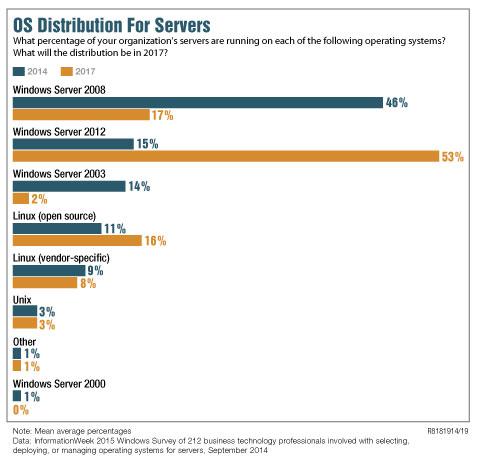

Windows versus Linux is the longest-running skirmish between open source and proprietary software. It's also now largely moot. As virtual machines become the default application environment -- and our latest InformationWeek State of the Data Center Survey finds 64% of respondents will have half or more of their production servers virtualized by the end of 2015 -- the underlying guest OS doesn't much matter. But as one area of contention subsides, many more arise. Technologies such as private cloud stacks (OpenStack, vCloud) and application containerization on low-power, non-x86 systems could shift the server balance. Open source software is making headway in three critical areas important to people running enterprise data centers: cloud stacks, software-defined networks, and big data platforms.

Let's look at each.

Cloud stacks: VMware still the default

Cloud stacks are perhaps the most visible software category in the data center for which open source presents a viable challenge to proprietary systems. Red Hat CEO Jim Whitehurst rightly characterizes the cloud as a disruptive force. "And in those paradigm shifts, generally new winners emerge," says Whitehurst. If Red Hat and other advocates have their way, OpenStack will be the standard cloud platform for service providers and enterprises alike.

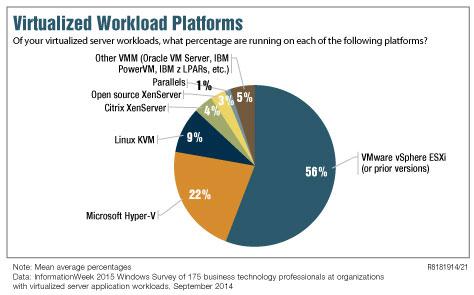

Despite abundant media hype, however, OpenStack faces an uphill battle. VMware is the de facto virtualization standard for almost two-thirds of enterprise IT organizations, and the company is building on that foundation. Although VMware faces competition on two fronts -- Microsoft Azure (proprietary) and OpenStack (open source) -- make no mistake, within the enterprise, it's still a David vs. Goliath situation.

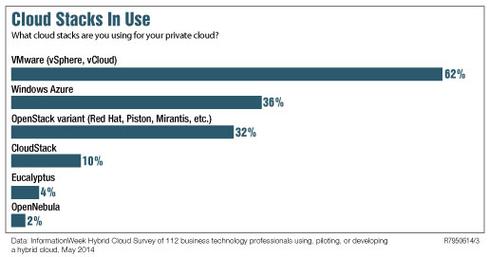

A recent InformationWeek survey of those using, piloting, or developing a hybrid cloud found OpenStack trailing VMware by 30 points. Although OpenStack has made progress, with nearly one-third of respondents using an OpenStack variant, its penetration remains almost identical to Azure's. Results from our 2014 Private Cloud Survey are less kind to the open source cloud stack. While 65% of respondents use VMware as part of their cloud designs, only 18% check in with Red Hat, and a mere 7% use OpenStack.

Figure 2:

The data isn't surprising when you consider that, for many enterprises, a private cloud featuring such niceties as self-service provisioning and automated workload migration is an extension of the existing virtual server infrastructure -- over which VMware has held sway since effectively creating the software category (at least on x86 platforms) a decade ago. And VMware isn't sitting still. The company is aggressively developing its own cloud stack replete with virtual networking and storage, infrastructure automation, workload orchestration, and public-private cloud integration. In fact, in an exclusive interview after his Interop keynote, CEO Pat Gelsinger

disputed the notion that hypervisors are a commodity. "I will happily tell you why vSphere is the best product," said Gelsinger. "It's the best hypervisor. It has features, like DRS [dynamic resource scheduler] and HA [high availability] and so on that aren't replicated in any of the KVMs or Hyper-Vs or anything else." Figure 3:

Gelsinger also emphasized VMware's work beyond the hypervisor -- including integrating OpenStack into predominantly vSphere environments. "We are adding support for the OpenStack compute resource Nova APIs to vSphere for management and vCAC [vCloud Automation Center] at the provisioning level," he said. "We can provision into the OpenStack consumption APIs as well."

VMware's work with OpenStack acknowledges that IT wants the flexibility of a multi-cloud environment. "We're embracing [OpenStack] APIs at multiple levels of our products and saying we will increasingly support these open interfaces," said Gelsinger.

In fact, at this year's VMworld, the company delivered on that promise by releasing its own OpenStack distribution for use within vCenter; see a summary of the announcement here. VMware executives cited cloud developer's preference for OpenStack's open, extensible API as motivation.

The strategy of building a cloud platform from proprietary components while supporting enough open APIs to peacefully coexist with OpenStack in a multicloud data center makes sense, but it's primarily a defensive maneuver to prevent defections as companies build native cloud applications -- and the infrastructure to support them.

VMware brings a $1 billion-plus annual R&D budget to this competition, but open source advocates are undeterred. They say there's plenty of corporate money behind open projects and point out that most public cloud services are built on a foundation of open source software -- even if, in the case of Amazon and Google, they don't run OpenStack per se. OpenStack proponents also note broad industry support for the project, with more than $10 million in funding from eight platinum members and 19 gold members that each pledge $500,000 and $200,000, respectively, to the OpenStack Foundation annually.

In talking about open source innovation in cloud software, specifically hot new projects like Docker (application containerization) and Mesosphere (pan-data center resource aggregation and administration), Red Hat's Whitehurst puts it bluntly: "There's a ton of cool stuff going on, but that's only happening with Web 2.0 companies, and it's all happening in open source." Whitehurst echoes early evangelists, saying that open source is a superior and scalable model for innovation when users, developers, and vendors are all involved in defining and solving software problems.The big winner in this skirmish is IT.

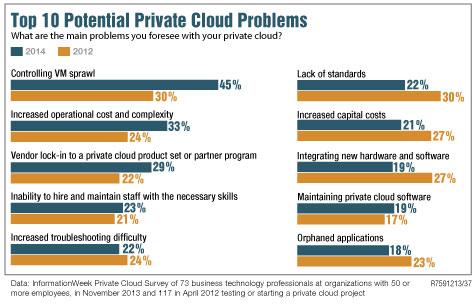

Figure 4:

Key benefits from open source cloud stacks are better interoperability and lowered risk of vendor lock-in. Indeed, vendors themselves often cite these reasons for supporting open source projects. Case in point: IBM's announcement of premier-level sponsorship for OpenStack. IBM believes that "fostering an industry-wide, open cloud architecture and simplifying how applications are built and deployed" will drive broader cloud adoption, writes Angel Diaz, IBM's VP of Open Technology and Cloud Performance Solutions. IBM sponsors OpenStack as part of its active role in "driving widespread adoption of cloud technologies based on open standards to enable interoperability and avoid vendor lock-in."

IT is getting more concerned about lock-in. While only 29% of respondents to our Private Cloud Survey cite vendor lock-in as one of the main implementation problems they anticipate, that's up seven points since 2012. Standards are particularly important when building a hybrid cloud mixing public and private services. Of those responding to the InformationWeek Hybrid Cloud Survey using, piloting, or developing a private cloud, 62% have or are building the ability to move applications and data between public and private clouds. However, while their internal cloud is most likely to be based on VMware, externally they more often use Microsoft Azure or AWS. Although this doesn't augur well for OpenStack (or vCloud Hybrid Service, for that matter) it does reinforce the need to address lock in and multicloud integration and management (a topic we cover in depth in this report).

Figure 5:

Whitehurst told us that one way companies are hedging their open vs. proprietary cloud bets is by building a parallel greenfield infrastructure for new, cloud-optimized applications. "If you look at cloud as an incremental baby step from your existing application in a virtual environment with a few more management tools, it probably doesn't make sense to rethink your infrastructure," he says. "But if you look at where most new applications are getting built, they're happening in an open infrastructure." Although Whitehurst does see companies improving existing virtualization systems for legacy (largely Windows-based) applications, he says they draw a distinction between these and what might be called "native cloud" applications.

Gelsinger would counter that OpenStack is more of an open cloud framework than product, and indeed, VMware's OpenStack distribution bolsters that viewpoint in that it can include both open source and closed source products. VMware's cloud management platform does likewise and will increase its support of open APIs. In other words, "we're open, too.'"

Bottom line: The zest with which big vendors are scrambling to embrace OpenStack confirms that it will become the lingua franca of clouds, defining the interfaces and APIs that allow different cloud systems, whether proprietary like AWS and vCloud or open source like Mirantis, Piston, and Red Hat OpenStack, to interoperate. That doesn't mean, however, that enterprises will use pure OpenStack.

Software-defined networks

If cloud stacks are the front line in the open source/proprietary software battle, SDN is the left flank. Once again, VMware is a key participant. However, the definition of "SDN" is

still so unsettled that the lines between open source and proprietary software are even more muddled than with OpenStack. Proprietary networking products invariably use standard protocols and often incorporate open source code -- as the widespread consequences of the OpenSSL Heartbleed bug painfully demonstrated.

The complexity is compounded since the debate happens on four architectural levels:

>> Within the hypervisor and its associated virtual switch, the issue is largely settled. The industry has rapidly consolidated its support for Open vSwitch (OVS) in preference to closed alternatives like Cisco's Nexus 1000V or the virtual switches built into vSphere and Hyper-V. >> Physical Layer 2 switching and flow control. Here the debate centers on OpenFlow and whether a hard separation between physical network data and control planes is necessary, and the pros and cons of replacing conventional switch fabrics using integrated (and closed) software with a central OpenFlow controller. As we point out in our SDN: Physical vs. Logical report, OpenFlow deals with physical network devices and ports and the flows among them. However, as more IT workloads become virtualized, an increasing percentage of data center traffic is initiated by -- and flows among -- virtual ports and switches. And in the virtual world, you don't need OpenFlow to get the benefits of a software-defined and automated network. And don't let vendors conflate the two.

Aside from the question of whether OpenFlow is even necessary in enterprise data centers, Network Computing contributor Ethan Banks points out that its "openness" is nuanced because the standards process is actually closed, even though the results are public.

>> Layer 3 virtual networks. This is still the Wild West of technology, with abundant choices, no clear winners, and competing architectures: one using virtual overlays to an Ethernet fabric substrate, the other relying on an OpenFlow controller to manage all layers of the network stack. The most widely known, if not yet popular, overlay is VMware's mostly proprietary NSX.

We say "mostly" because NSX does use OVS and standard tunneling protocols, such as VXLAN, STT, and NVGRE. However, as we discuss in depth in our Network Computing SDN Smackdown issue, there's no shortage of proprietary overlay alternatives, including products from Midokura, Plexxi, and Plumgrid. All of these include some level of support for the OpenStack Neutron network plug-in, meaning virtual network resources on OpenStack can be managed and controlled within a broader overlay network design.

>> Layer 7 network APIs and physical and virtual network resource management and automation. Network controllers and northbound APIs are seeing especially active development, debate -- and uncertainty. Network equipment vendors realize that the standards, APIs, and protocols used to program and control the network have implications for every device on the network.

The most important open source effort in this realm is OpenDaylight, a project broadly supported by industry heavyweights that made its first public code release this spring. In fact, the OpenDaylight Hydrogen project won the 2014 Best of Interop Grand Award because it's not only a strong product, it shows what industry-wide collaboration can deliver. Hydrogen is a modular SDN controller that can support any number of southbound interfaces to control both hardware and software networking products as well as northbound interfaces accessible to a variety of SDN applications.

Another open effort to address virtual network application interoperability is the recently announced Open Network Function Virtualization (OP-NFV) project under the Linux Foundation. The goal is to establish an open source reference platform to advance the evolution of NFV and ensure performance and interoperability among multiple open source components. The software's initial focus will be open APIs for NFV infrastructure management and automation that bridge the gap between virtual infrastructure platforms, such as vCenter with NSX or OpenStack, and higher-level network services, like mobile or tunneling gateways, firewalls, content filters, or monitoring services.

OpenDaylight's most significant commercial competitors are Cisco's Application Centric Infrastructure (ACI), along with the new Cisco APIC controller, so far only available as a hardware appliance, and VMware NSX, an expensive add-on to vCloud Suite. OpenDaylight also has open source competition in the form of OpenContrail, a product Juniper acquired and later released as a public project, and the Open Networking Foundation (ONF), custodians of the OpenFlow standard. ONF has working groups developing an architectural framework, northbound interfaces, configuration and management specifications, and interoperability guidelines that could ultimately be incorporated into an open source OpenFlow controller like Floodlight. That could result in a viable alternative to OpenDaylight or APIC.

Bottom line: SDN adopters are likely to favor open source projects, if developers can keep complexity under control.

Big data platforms

Open source software, primarily via the Apache Hadoop project, is arguably the reason big data software has achieved widespread use. Although the technology for large, distributed databases, parallelized data processing and search, and distributed resource management and scheduling long predate it, Hadoop, the open source framework for distributed processing of large data sets across clusters of computers, is the software that launched not just a thousand but perhaps millions of implementations and spawned an ecosystem of ancillary big data software.

Although the source code is freely downloadable, most enterprises use either a commercial Hadoop implementation, popular ones being Hortonworks, IBM InfoSphere, Intel, MapR, Pivotal (EMC) Greenplum, and Sqrrl, or a Hadoop service, like AWS Elastic MapReduce, Cloudera, or Google Cloud Platform.

Of course, the big advantage of a common data platform is that applications should be portable among implementations. Indeed, Spotify made headlines last fall when it migrated its Hadoop infrastructure from Cloudera to Hortonworks.

Even Oracle has been forced to embrace Hadoop. It offers an integrated Hadoop appliance and data integration software to transfer data between Hadoop and Oracle's SQL database, along with its own NoSQL alternative.Another popular big data platform is SAP's in-memory HANA. Unlike Hadoop, HANA is a relational database with full ACID compliance; Hadoop HBase has only limited ACID properties. HANA provides very high performance due to its in-memory design, yet still scales to multiterabyte data sets and has become the model for other in-memory database systems. We expect to see more competition from open source alternatives like Hazelcast and VoltDB.

Bottom Line: Remember, you don't need Hadoop or its alternatives just because your data has outgrown Excel. Unless the data set measures in terabytes or the system must rapidly ingest large data streams from many sources, big data platforms are overkill. However, when the time comes that you do need such a platform, open source projects have brought them within financial reach of most companies.

For enterprise IT, open source purity is neither possible nor desirable. Instead, demand interoperable, flexible products resistant to lock-in. Support vendors that back open source projects, use standard APIs and data formats, publish their own APIs and data formats, and build a variety of connectors. Evaluate any potential code in 12 areas: features, performance, reliability, scalability, usability, interoperability, adaptability and programmability, security, vendor and community support, software ecosystem, technology road map, and price. And trust that when proprietary vendors and open source projects coexist peacefully, everyone wins.

Get the new issue of

Network Computing.